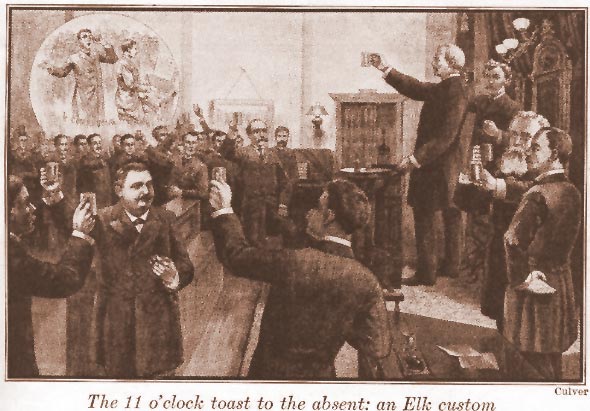

At every meeting of the BPOE, and every social function, when the hour of 11:00 p.m. tolls, the Lodge conducts a charming ceremonial known as the “Eleven O’clock Toast.” In fact, the clock tolling the eleventh hour is part of the BPOE official emblem, and is directly behind the representation of an elk’s head in the emblem of the Order.

You have heard the tolling of 11 strokes. This is to remind us that with Elks, the hour of 11 has a tender significance. Wherever Elks may roam, whatever their lot in life may be, when this hour falls upon the dial of night, the great heart of Elkdom swells and throbs. It is the golden hour of recollection, the homecoming of those who wander, the mystic roll call of those who will come no more.Living or dead, Elks are never forgotten, never forsaken. Morning and noon may pass them by, the light of day sink heedlessly in the West, but ere the shadows of midnight shall fall, the chimes of memory will be pealing forth the friendly message,”To our absent members.”

Origin of the Toast In regard to the Elks’ 11 O’Clock Toast and its origin, we have to go back long before the BPOE came into existence. One of the main contributions of Charles Richardson — in stage name of Charles Algernon Sidney Vivian and founder of the American branch of the Jolly Corks — was to deliver into the hands of newborn Elks the rituals and traditions of a fraternal organization started in England around 1010 A.D., the Royal and Antedeluvian Order of Buffaloes, to which he belonged prior to coming to New York.

The RAOB, or Buffaloes as we shall henceforth refer to them, also practiced an 11 O’Clock toast in remembrance of the Battle of Hastings in October of 1066. Following his victory, William of Normandy imported a set of rules, both martial and civil in nature, to keep control of a seething Norman-Saxon population always on the edge of a revolution.

Among those rules was a curfew law requiring all watch fires, bonfires (basically all lights controlled by private citizens that could serve as signals) to be extinguished at 11 each night. From strategically placed watchtowers that also served as early fire-alarm posts, the call would go out to douse or shutter all lights and bank all fires. This also served to discourage secret and treasonous meetings, as chimney sparks stood out against the black sky. A person away from his home and out on the darkened streets, when all doors were barred for the night, risked great peril from either evildoers or patrolling militia.

The hour of 11 quickly acquired a somber meaning, and in the centuries that followed, became the synonym throughout Europe for someone on his deathbed or about to go into battle: i.e.”His family gathered about his bed at the 11th hour,” or “The troops in the trenches hastily wrote notes to their families as the 11th hour approached when they must charge over the top.”

Thus, when the 15 Jolly Corks (of whom seven were not native-born Americans) voted on February 16, 1868, to start a more formal and official organization, they were already aware of an almost universally prevalent sentiment about the mystic and haunting aura connected with the nightly hour of 11, and it took no great eloquence by Vivian to establish a ritual toast similar to that of the Buffaloes at the next-to-last hour each day.

The great variety of 11 O’Clock Toasts, including the Jolly Corks Toast, makes it clear that there was no fixed and official version until 1906-10. Given our theatrical origins, it was almost mandatory that the pre-1900 Elks would be expected to compose a beautiful toast extemporaneously at will. Regardless of the form, however, the custom is as old as the Elks.

A Note from Mike Kelly

It is very heart-warming to Elks with a deep interest in the history and “roots” of our beloved Order to note the re-awakened appreciation for the many and beautiful variations — prose and poetry — in the Eleven O’Clock Toasts of the yesterElks, especially coming from those of a decidedly younger persuasion who have only come into our ranks in modern times and were understandably unaware of what could be done with the bittersweet sentiment of the hour of eleven when given free rein by the great orators and theatrical luminaries who populated Elkdom prior to the introduction of the current standardized ritual toast. We encourage them to continue expanding their horizons, and ask that Lodges and individual Elks assist them by compiling as many colorful Toasts from each’s own past and sharing these “gems” wherever possible.

While we also ask that the archives of the Grand Secretary’s office be kept in mind when such discoveries are brought back into the light of day, we hope that all will understand if we cannot take thousands of toasts, sort through them and polish them up, have them printed and bound, and finally distribute them when there is no staff, work-hours or budget set aside to accomplish what would recognizably be a formidable task — just one historian delving back through the dusty corridors of antiquity in the few moments allowable between more mundane duties because of an innate fondness for the magic and mystery of the antlered past.

What we can promise is that we will maintain a permanent, distinct Eleven O’ Clock Toast file that will be available for reference to any visitor so that any contributions will not be lost to oblivion. And, in a tip of the hat to the new vista whose doorways are the Elks computers nationwide, we will get noteworthy additions to the collection to pop up on your screens as frequently as time permits to keep this revival humming. Perhaps the next time you hear the Toast of Eleven on a visit to another Lodge’s social function, it will be the freshened echo of words spoken at the turn of the century in tribute to absent colleagues of America’s greatest fraternal organization — B.P.O. Elks, “The Best People On Earth.”